Kaibigan,

In my experience, there have been two things that always ruined my theatre-going—a very bad production and sitting in the audience with students who have been required (read: forced) to watch the performance. That premonition was sinking into me as I lined up at the entrance of the Rizal MiniTheatre with more than a fistful of Ateneo freshmen chattering non-stop up to the last second before the anthem was sung. Like children being told to eat their vegetables, an audience being force-fed theatre, even with the best intentions, often triggers rebellious behavior. I’ve seen this before. A well placed disruptive smart aleck comment released in the height of a dramatic moment during the play could ruin everything that the actors worked for. And that’s how, sometimes, a rowdy audience can trigger a dismal performance. I was bracing myself for a rough matinee.

How lovely to have been proven wrong.

The audience stayed alert, critical, and respectful all throughout the three plays that ran to about 2 hours. More than that, they gave back in equal measure by applauding in appreciation for the truthful and generous performance by the Entablado’s roster of actors.

In part, the credit goes to the short introduction delivered before the show by the plays’ director, Jethro Nino Tenorio, for the young crowd to “listen carefully” to the plays. His reminder that, as freshmen, the audience was expected to act mature was well received mainly because it felt sincere and sensible; delivered with humor and without condescension. But most of the credit should go to the energetic and engaging performances by the young cast of Entablado’s Tarong (Tatlong Dula ng Pagtawid).

It is difficult to cavil with earnest performances such as the one displayed by these young actors. Notable was the ensemble work of the three actresses in J. Dennis Teodosio’s Pobreng Alindanaw. I’ve seen this play—about two dragonflies unsatisfied with their looks and wanting to transform themselves into a butterfly—performed by three men in glittering make-up. You can imagine the gay sensibility piled high. Because of the fable-like setting, the snappy repartee, and the contemporary allusions, there is a tendency for this play to be performed like it was a Saturday gay club stand-up: all for laughs. It was refreshing to see three young actresses tackle the dialogue from a wider perspective. In this incarnation, Beauty, the stunning butterfly (Anne Mariel Dionisio), Chubbs, the carabao Dragonfly (Portia Marie M. Silva), and Tiny, the needle Dragonfly (Patricia Ruth Pena), were imbued with charisma. The actresses performed the physical comedy with elan (not slapstick at all); and they delivered their comic punchlines with professional precision. The fact that they didn’t portray the insects sounding like women in drag enlarged the scope of the play’s skimming explorations on beauty, identity, and peer pressure. A more unified costume from Regina Regala would have done wonders to the visuals. And the moving platforms should have remained where they were during the asides. But these small blemishes did not detract the audience from enjoying the show. If the play goes on again, watch out for the musicale numbers. They were, in the words of the dragonflies, “Faaaaabe-ulous!”

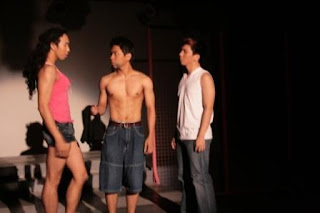

In contrast, the third play, Chris Martinez’ Baclofen, tackled violence and sexuality head-on. Tenorio’s direction was direct, unapologetic, and extremely brave in the physical portrayal of same sex couplings. There were gasps (and the young man to my left was physically squirming) all throughout that long kissing scene (1 minute 48 long seconds on my watch, to be precise) between David (Sergio Luis A. Gahol) and Jonathan (Kalil Christian Almonte). But everyone in the audience seemed to understand that it was a necessary portrayal in order to be aware of how, in ordinary circumstances, we react to the physical manifestations of sexual diversity. In several scenes in Martinez’ play, the character of Jonathan answers questions thrown at him by rephrasing his answer in question form reminiscent of Edward Albee’s The Zoo Story. The writing follows Albee’s signature ambiguity in delineating character motivations. The text does not say, for example, why David prefers Jonathan over Naomi (treacherously fleshed out by the long legged and Salome be-wigged Ariel Acuna Diccion). Is it because David prefers a straight-acting gay male over a mujerista, a transvestite? When David is unable to name his love for Jonathan, the text gives a clue as to David’s perception of masculinity. What are the implications of being Top (gay reference to the Dominant sexual partner, i.e., penetrator) as opposed to being Bottom (the submissive sexual partner, i.e. receiver)? Among the three, this play is the most tricky to direct because the themes are merely hinted at by the text. A strong understanding of the characters emotional arches is a grave prerequisite. Irony, too could have been better exploited. Surely, there were missed moments of tenderness amidst all the violence. Better picturizations would have helped clarify motivations. Extra coaching would have helped the actors discover basic truths in the drinking scene. Didn’t Naomi express his preference for sweaty, grimy, earth-smelling men? Sensory exercises would have expanded the texture and sensual nature of the scenes. How would a rough trade like David sit, drink beer, play pusoy? It would have been informational for the audience if he kissed Naomi, if only to contrast this with his kiss for Jonathan. There’s a hypnotic scene in the play where Jonathan dons Naomi’s wig after he has killed his tormentor and his would-be saviour. He looks in the mirror and then cries out in pain. What is it to be a man or a woman? If the production should go back to this scene, I think they will discover the key that will unlock the full possibilities of the play.

Compared to the complex writing of the two plays previously mentioned, Ramon C. Jocson’s Bulong-Bulongan sa Sangandaan seems too simple in its reliance on the single revelation in the end. This Palanca-awarded play may seem dated in the light of other more successful treatments of the trick employed in movies like The Departed or any of the Shake, Rattle and Roll installments. I am glad that Entablado is doing Jocson, if only to encourage him to write new material. Despite the weakness of the material, the actors did their best to flesh out human characters. The play devotes three-fourths of its length in expounding their back stories. Peryo (Joseph Anthony M. Cuadro) is longing for his departed wife; Andong (Andrie Ellison Y. Corpuz) is a farmer forced to find work in the construction site in the city; and Loloy (Jose Antonio P. Javier) is a happy boy who loves to sing and dreams to study to better support his siblings. The male and female security guards were consigned to connecting the scenes. Although, Jocson writes in a conflict about the delay of their salaries, it is rudimentary. It didn’t dove tail with the real issue of the story. It was not a real conflict: merely another aspect of the exposition. Moreover, the secret of the play is revealed too early. In the first scene, when the lights keep blinking as a prelude to the entrance of one of the pahinantes, there is no doubt that the three main characters are ghosts. Like a magic trick prematurely explained, the surprise is ruined. Too many hints can disappoint. Although Francisco E. Chung, did a great job providing ambiance and illumination to the two other plays, he may need to re-plot the lights to Bulong-Bulongan.

No comments:

Post a Comment